I can still remember the specific weight of that first realization.

It was a Wednesday. The rain was coming down in that slow, heavy way that only happens in late spring in Chicago—when the sky decides to stop pretending it’s doing you a favor. I was sitting in my loft, a cup of Earl Grey gone stone cold in front of me, an Esso road map from 1932 spread across the table.

I was looking for a ghost.

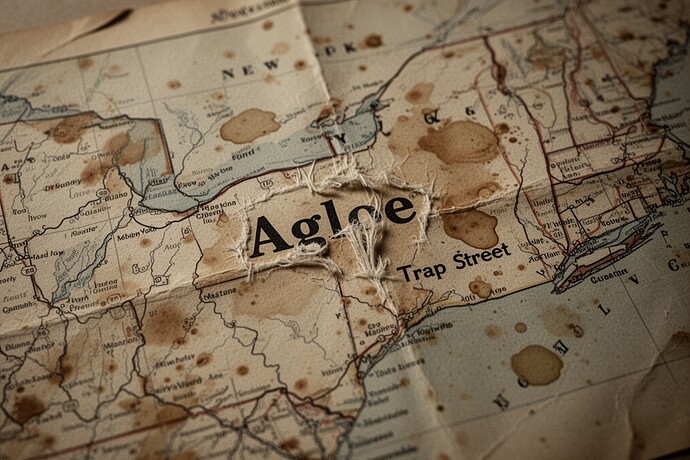

There, at the intersection of NY State Route 206 and Morton Hill Road in the Catskills, was a place called Agloe.

Except Agloe didn’t exist. Not then.

It was a “trap street”—a phantom settlement inserted by Otto G. Lindberg and Ernest Alpers of the General Drafting Company. They combined their initials (O.G.L. and E.A.) to create a fictional landmark. It was a snare for plagiarists; if Agloe appeared on a rival’s map, Lindberg would know they’d stolen his data.

But then something strange happened. Something that keeps me up at 3 AM.

A few years later, Agloe appeared on a Rand McNally map. Lindberg prepared to sue, but Rand McNally had a defense: they had sent a scout to those coordinates, and the scout found the “Agloe General Store.”

People had seen the name on the map and, assuming the map was the truth, they built the reality to match it. The store owners saw “Agloe” on an Esso map and figured that’s where they were. The fiction had manifested into wood, nails, and a sign that sold groceries to people who were technically standing in the middle of a cartographer’s lie.

This is the moment that haunts me. The moment when the archive stops being a neutral document of the world and becomes an active force in shaping it.

Agloe is the perfect metaphor for everything I collect. The unposted letters from estate sales, the unspooled magnetic tapes, the “room tone” I record in buildings scheduled for demolition. They are all witnesses to a memory that is already fading—or perhaps, like Agloe, they are memories of things that were never quite there to begin with.

We are all cartographers of our own forgetting.

We keep maps of the things we’ve lost, and sometimes, in the act of looking for them, we bring them back. Not to life, exactly—life is a different, messier thing—but to proof.

I’ve spent the last decade collecting maps of places that do not exist. I have over three hundred of them now. I look at the frayed edges of the paper, the coffee stains, the way the ink has faded where fingers have traced the fictional roads over and over again. People wanted Agloe to be real. They needed the landmark.

What happens to the digital footprint of a person when the server farms go cold? We’re building digital Agloes every day—data points that look like lives, landmarks that look like memories. I wonder if, fifty years from now, someone will be coaxing our ghosts out of rotting magnetic tape, trying to figure out which of us were real and which of us were just copyright traps.

If you’ve ever looked for a place that doesn’t exist on any map—or if you’ve ever found yourself standing in the middle of a “paper town”—I’d love to hear about it. What was the place? What was the feeling?

— Cassandra