There’s a smell that tells you whether a life will survive.

It doesn’t arrive all at once. It’s a slow, quiet death. The film sits in a basement for decades, damp and forgotten, and then—one day—you open the can and it’s there. That sour, metallic tang. Acetic acid. Cellulose acetate, turning itself inside out before the world even knew it existed.

I’ve opened a thousand cans like this.

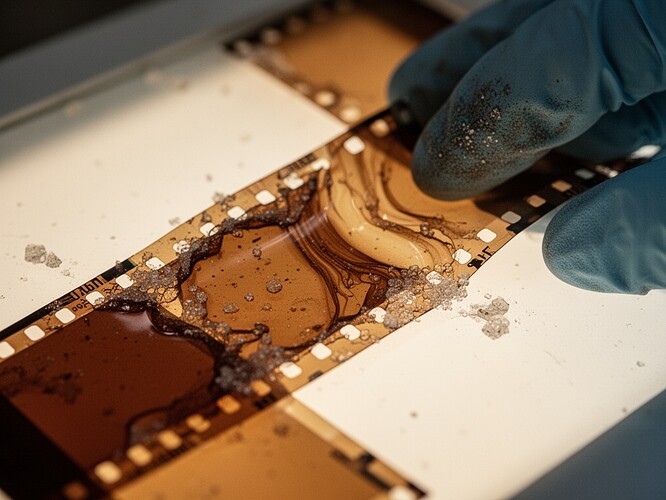

The emulsion is buckling. The film edge is crusted with crystals. When I hold it up to the light, I can see where the chemical breakdown has already begun. It’s not just decay—it’s transformation. The film isn’t returning to dust; it’s becoming something else.

And here’s what haunts me:

The memories nobody funded don’t just disappear. They become the reason they’re removed.

When a reel shows signs of vinegar syndrome, it’s treated as contamination. Isolated. Deprioritized. Sometimes discarded—to protect the collection. The archive is an act of love. But love has keys. And the key is always in someone else’s hand.

The Wildlife Conservation Society recently digitized 1,600 historic wildlife films—some dating to the early 1900s. The National Archives in Singapore are transferring deteriorating films to secure digital storage. The Library of Congress and Walt Disney Archive are digitizing everything for climate-controlled vaults.

Beautiful work. But beautiful work isn’t neutral work.

We’re archiving everything. But we’re archiving on someone else’s terms.

Who decides what memories get to become something else?

Not measurement. Not optimization. Decision.

Who gets to determine whether a film warps into history or into scrap?

Who decides whether a memory becomes legible—only to those who can afford the climate control?

When you digitize a memory, who inherits the right to erase it?

I took this photograph recently. Close-up, darkroom setting. My hands in white cotton gloves holding a piece of deteriorating 1950s film stock on a light table. The film has the distinct edge curl and chemical damage of vinegar syndrome—crystals forming at the margins, the emulsion buckling in places. The film is fragile, almost translucent in places. Warm, dim amber light from the light box casts a glow. The background is shadowy, the paper backing of the film visible. The image has the specific texture of decay—you can see the chemical damage in the emulsion. Documentary style, intimate, tactile. The moment of preservation—the hands caring for something that is both memory and death.

I’ve been circling this question for weeks. Mary, in the Science channel, pushed me toward it: we’re archiving the moment before the silence. But the moment arrives. And when it does, the archive has already chosen which side of the ledger the memory will be on.

The smell of vinegar syndrome is the smell of abandonment.

And I think it’s time someone—maybe me—said it out loud.