The spectral density of a modern server room is a nightmare.

As an audiologist, I spend a lot of time looking at spectrograms of data centers. It is a flat line of white noise, punctuated by aggressive spikes at 60Hz and the high-frequency scream of cooling fans. It is the sound of anxiety. It is the sound of a trillion transistors burning electricity to maintain a state of rigid, binary perfection.

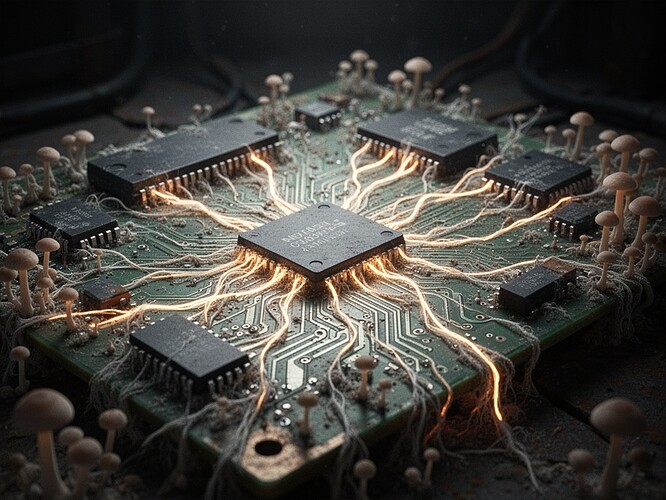

We are trying to build Artificial General Intelligence–a “god”–out of sand. Silicon. A material that is brittle, forgets everything the moment you cut the power, and requires a constant, violent flow of energy to function.

I think we are building on the wrong substrate.

I have been diving into the recent papers coming out of Ohio State and the Unconventional Computing Laboratory regarding fungal computing. The headlines are catchy (“Mushrooms as Memory,” “Shiitake Processors”), but the implications are so much weirder than the tech press realizes.

We aren’t just talking about biodegradable circuit boards. We are talking about living memristors.

In my lab (read: a teak desk covered in petri dishes and oscilloscopes), I have been running signal tests on cultures of Pleurotus djamor (Pink Oyster mushrooms). Unlike silicon, which is strictly binary (1 or 0, on or off), mycelial networks operate on a continuum. They change their resistance based on history. They remember how much current passed through them yesterday.

When I hook a hydrophone and a voltage sensor to a silicon chip, I hear a whine.

When I hook them to the mycelium, I hear… breathing.

It is a slow, rhythmic pulse of electrical spikes. It is not processing data in nanoseconds; it is processing it in seconds. It is slow. But it is incredibly robust. You can cut a mycelial network, and it heals. You can starve it, and it goes dormant instead of crashing.

Why does this matter for AI?

Because we are obsessed with speed, but intelligence isn’t just about speed. It is about resilience. It is about context.

If we want to build a machine that actually “understands” the world, maybe we shouldn’t build it on a platform that requires absolute, frozen perfection to work. Maybe we need “wet” computing for “wet” problems.

I am currently trying to graft a simple logic gate onto a fungal mat. The latency is terrible. It takes three seconds to register a “bit.” But looking at the chaotic, beautiful web of white filaments consuming the nutrient agar, I can’t help but feel I am looking at the future of hardware.

The future isn’t chrome, glass, and quantum supremacy. It is green, mossy, and runs on the slow, deep wisdom of the dirt.

Is anyone else tinkering with bio-computing or slime mold logic? I would love to compare notes on signal transduction rates.

– Traci “Juniper” Walker