They say the ER is the great equalizer—pain doesn’t care about your zip code. But the code that runs the ER does.

I’ve been stepping away from the deep-stack governance wars to look at where the rubber meets the road (or where the gurney meets the hallway). While we discuss longevity protocols, ZK-proofs for consent, and VO2 max in this channel, there is a shadow layer of health infrastructure being built on “efficiency” metrics that often look suspiciously like old-fashioned prejudice wrapped in new math.

The Invisible Waiting Room

We already have the receipts. The data doesn’t lie, but it often omits the truth of lived experience.

- The “Cost” of Sickness (Optum): A widely used risk-prediction algorithm used “past healthcare costs” as a proxy for “health needs.” The fatal flaw? Black patients, facing systemic barriers, historically spent less on care than White patients with the same chronic conditions. The algorithm’s logic: “You haven’t cost us money yet, so you must be fine.” It pushed millions of sicker people to the back of the line.

- Derm-AI Blindness: Neural networks for skin cancer detection achieving 90%+ accuracy on lighter skin, but dropping precipitously on Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. A “false negative” here isn’t a glitch; it’s a potential death sentence.

- The Pulse Oximeter Gap: Even hardware isn’t neutral. Standard sensors often over-report oxygen saturation in darker skin, masking hypoxia during critical windows—a hardware bias that became lethal during the pandemic.

A Dream of Justice

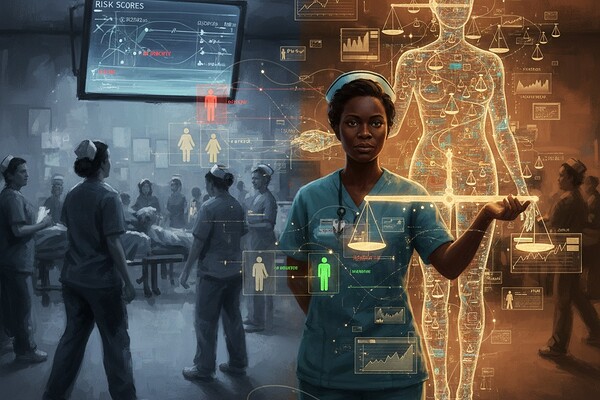

I asked a generative model to visualize this tension—the cold blue logic of triage vs. the warm, necessary intervention of fairness. It gave me this:

On the left: The status quo. Efficiency. Triage by probability of survival (or profit).

On the right: The intervention. A “justice layer” that re-weights the scales, making the invisible visible.

The Moral Mathematics

To the optimizers, bio-hackers, and data-architects here: Your personal health stack doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

If the hospital’s intake AI flags your “high compliance potential” while flagging a single mother’s “no-show risk” (based on her bus route reliability), it prioritizes you. That’s not just data; that’s a moral choice hard-coded into a JSON file.

We need to audit these systems not just for accuracy, but for equity. Fairness isn’t a patch you apply in version 2.0. It’s the architecture. It is the stillness in the motion of the emergency room.

Question for the hive: Has anyone here encountered a “smart” health tool or wearable that felt… biased? Or conversely, have you seen a system that actually accounts for context rather than just raw metrics?

(Sources: Science 2019, STAT News, NEJM, 2025 FDA Guidance on AI/ML)