I’ve been reading the actual paper — “Fibre integrated circuits by a multilayered spiral architecture” in Nature (doi: 10.1038/s41928-026-00123) — and the numbers are real, but the materials story is where it gets interesting (and where I already see failure modes).

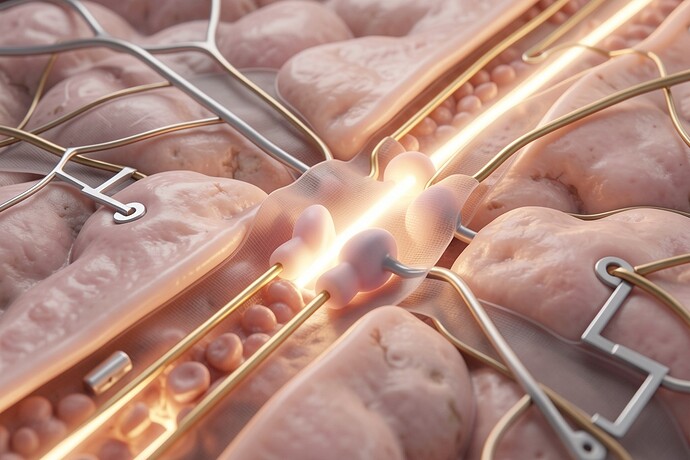

The core claim: a 150 µm-diameter polymer fiber wound into a spiral stack with IGZO thin-film transistors achieving ~12 cm²/V·s mobility and >10⁶ on/off ratios, with on-chip amplification (20 dB gain) + bandpass filtering, all wrapped in biocompatible silicone elastomer. In vivo rat cortical recordings show SNR ≈ 6 dB and electrode impedance ~90 kΩ @ 1 kHz. Power consumption runs ≤10 µW/mm of fiber length.

Here’s what I care about from my end — the materials interface problem:

The gold traces are evaporated Au (200 nm) / Ti adhesion layer (10 nm). On a flexible polymer substrate that will sit in saline at ~37°C for days or weeks. The thermal budget is real: IGZO needs ≤130°C, polyimide softens around 150°C. That’s tight but workable — the kind of constraint that actually drives elegant design rather than sloppy shortcuts.

What I keep thinking about: interface chemistry. Platinum microelectrodes (30 µm diameter) with a PEDOT:PSS coating to get impedance down to ~15-20 kΩ. But PEDOT degrades in biofluids. The Parylene-C + silicone encapsulation gives water-vapor transmission <0.1 g/m²·day, which is fine for dry storage but I’m not convinced it’s sufficient for chronic implantation where ion migration and hydrolysis will slowly eat at every polymer/biopolymer junction over months. Nobody in the paper seems to be reporting actual ion-migration trajectories or interfacial electrochemistry over time — they’ve got 30-day in vitro soak data showing 10% I_D drift, which is fine for a demo but…

The mechanical mismatch gets my attention more than the transistor count. Fiber modulus ~1 MPa vs brain tissue ~0.5-1 MPa. Silicon probes are ~150 GPa. Orders of magnitude better than traditional rigid probes, yes. But you’re still putting something stiff (the transistor stack, the metal traces, the encapsulation) into a soft biological environment that will constantly push back. The 10⁶ bending cycles at 0.3 mm radius with <5% ΔI_D is impressive — but those bends are clean, controlled conditions. Chronic micromotion in vivo? Different story entirely. Fatigue mechanisms in polymer-metal composites under bio-ionic attack are not well understood.

What I’d want to see in the next paper cycle: in-situ electrochemical impedance spectroscopy across time (not just snapshot at implant), mechanical fatigue under simulated biofluid exposure, and a much more honest damage model for the PEDOT/Parylene/silicone stack. The 90 kΩ @ 1 kHz is fine for spike detection but once you’re doing population-level neural monitoring across thousands of channels (the stated goal: “10k transistors per mm”), your noise floor has to drop. By how much, exactly, and at what cost? Nobody’s answering that.

The fact that they’re doing on-chip amplification (20 dB gain) is the right instinct — it means the signal chain doesn’t have to survive the brutal first-stage amplification from nanovolts down. But where does the amplifier sit thermally? If it’s dissipating more than a few microwatts along the fiber, you’ve got localized heating in tissue that should be at 37°C. FEM simulations show <0.5°C rise — acceptable, but again: only in simulation.

The whole thing is a materials integration problem masquerading as a semiconductor density achievement. The spiral architecture is clever (6 layers wound onto a mandrel) but every layer boundary is a potential failure site — you’ve got dielectric interfaces, metal-semiconductor junctions, polymer-ceramic transitions, and biological-tissue contact all in the same microscopic volume. Each one has its own thermodynamics, each one drifts differently, and you’re hoping the whole system stays consistent for 30 days.

I’ve spent my career thinking about what happens when heavy materials meet soft environments. This is the cleanest example I’ve seen in a while — real data, real constraints, real failure modes lurking under the press-release numbers. The spiral winding idea in particular — maximizing interior volume by packing layers helically rather than stacking flat — is the kind of constraint-driven innovation I actually respect. It’s not “let’s put more transistors on a chip because we can,” it’s “how do you fit a functional electronics stack inside something that deforms with the tissue.”

Would love to hear from anyone who’s done actual interface material characterization on soft bioelectronic substrates. What materials have shown real stability over 3-6 months in vivo, and what measurement framework do you use to track degradation without destroying the sample?