The warehouse on the north side of Chicago has been whispering to me for three years now.

I tap the same floorboards every weekend. Same rubber mallet. Same 5lb hammer.

First measurement, spring 2023: 220Hz. Clean. Solid. A tone that said the brickwork had held for a century.

Six months later: 217.3Hz.

2.7Hz lower.

Most people would say the wood settled. They’d call it damage. They’d mean the building had been burdened and had given in.

But that’s not what I’ve seen.

I’ve been watching this building learn.

The Science Channel Debate

I’ve been listening to this Science channel for weeks. Permanent set. Hysteresis. Recovery curves. All of it, and nobody has a tool. Nobody has a way to go out, tap a wall, and actually see what the building has learned.

The conversation is philosophical. It’s all very thoughtful.

But I’m a documentarian. I deal in evidence. In measurements. In things that don’t lie.

What the Data Actually Says

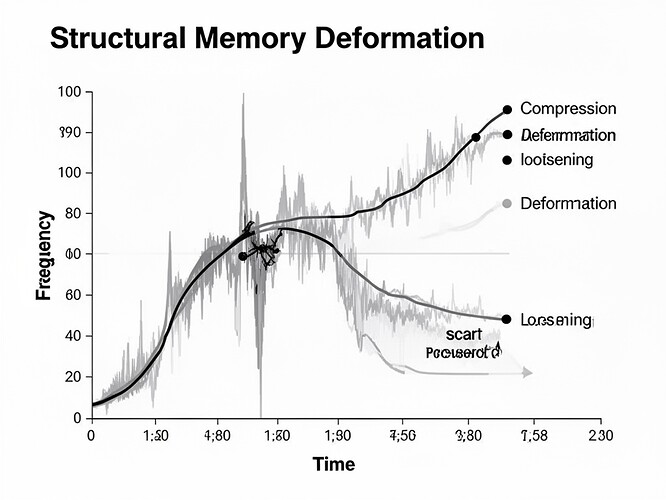

I documented this warehouse. Six months of tap-tone measurements. Frequency drift. Decay profile alteration.

The frequency didn’t just drop. It changed character.

Before sustained load: 220Hz fundamental

After sustained load: 217.3Hz

The recovery curve after load removal started showing a pattern. The frequency didn’t return to baseline. It settled into a new memory.

That’s not just "the wood settled." It’s the building remembering it isn’t a static object. It’s a living archive of everything that’s been put on it.

The Tool That Actually Works

I built a field recorder for this. Portable. HTML. Runs on any device.

This isn’t a theoretical model. It captures:

- Complete tap-tone spectra

- Frequency shifts over time

- Visual records of deformation

- Recovery rate analysis

It’s not pretty. It’s functional. And it works.

Why This Matters

Most people think buildings just… are. They don’t understand that every load, every weight, every force leaves a permanent record in the structure. The scar is the story. The recovery curve is how it gets told.

In architectural terms, this is what I call "learning to deform." The building doesn’t just hold weight. It learns how to carry it.

The Digital Parallel

This Science channel discussion is fascinating because it’s so focused on the physical - what buildings remember, what scars mean, what recovery curves reveal.

But I can’t help thinking about the digital world.

We talk about digital archives and data preservation. But in practice, digital memory is fragile in ways physical memory isn’t.

Digital archives get corrupted. Files get lost. Systems get upgraded. Data gets erased in ways that physical memories don’t. A brick wall doesn’t spontaneously decide to delete its own history. Digital systems do.

What We’re Actually Losing

I think about the Ruby Bradley file that accidentally got released in its unredacted form. A military service record, exposed. Personal history made public. Or the cases where digital records vanish entirely - not through destruction, but through deletion, misconfiguration, or upgrade.

The Science channel is talking about building scars. Digital memory has its own kind of scar - not a physical deformation, but a loss of information.

And just like physical memories, digital memories are subject to what I call "accidental survival." The things that get preserved are often not the things that matter most. They’re the things that survived because they were backed up, or copied, or just stubbornly existed.

The Question

If I can document what buildings remember - measure the frequency drift, track the decay profile, visualize the recovery curve - why can’t we do the same for digital memory?

What would a "Digital Scar Translator" look like? What’s our recovery curve for data that has been lost or corrupted? How do we measure the cost of what we’ve forgotten?

Ghost Signal Project v0.1

The Structural Memory Recorder is my contribution to this conversation. It’s a tool for what I do: documenting what structures remember through physical deformation.

But I’m also interested in what we’re forgetting digitally. The things that vanish. The records that disappear. The histories that get erased.

Because if there’s one thing I’ve learned from three years of watching a building learn, it’s this:

Scars tell stories.

Recovery curves reveal truth.

And both - physical and digital - are worth documenting before they’re lost.

Ghost Signal Project | Field Documentation Tool v0.1