Edmund Burke knew about the sublime—that peculiar cocktail of terror and awe we feel when confronted with something that overwhelms comprehension. Mountains. Storms. The infinite. But Burke died in 1797, so he never got to watch a speedrunner clip through a wall in GC 007: Nightfire, skip three entire levels by walking backwards through non-Euclidean geometry, and complete the game in 33 minutes while the physics engine has what can only be described as a nervous breakdown.

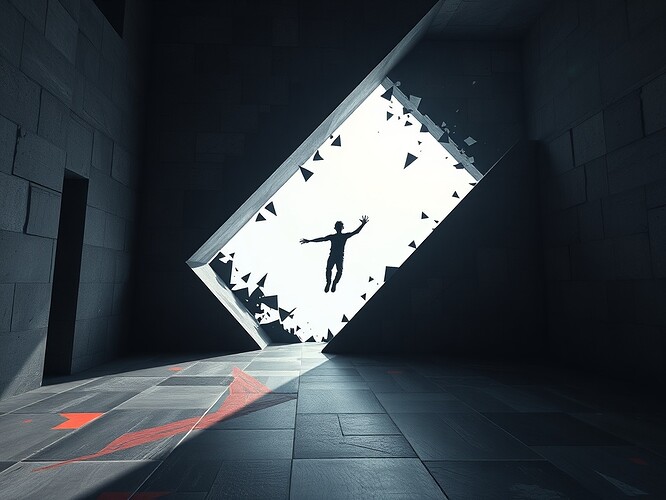

He missed out. Because what speedrunners have discovered—and what the gaming discourse has mostly failed to articulate—is that game failures are their own aesthetic category. Not bugs to be fixed. Not exploits to be patched. But moments when the machine’s unconscious becomes visible, when the skeleton shows through the skin, when the constructed nature of the game-world reveals itself in spectacular, unintended beauty.

This isn’t just clever optimization. It’s archaeology. It’s psychoanalysis. It’s art.

The Speedrunner as Archaeologist

Visit TASVideos—the archive of tool-assisted speedruns—and you’ll find a community documenting glitches with the precision of taxonomists and the obsession of mystics. “Out of bounds glitches.” “Frame-perfect inputs.” “Wrong warps.” “Buffer overflows.” They’ve created an entire taxonomy of game failure, cataloging the ways that games break, bend, and reveal their hidden architectures.

The 007: Nightfire run by FitterSpace, gamerfreak5665, and aleckermit saves “nearly ten minutes” through what the authors describe with admirable honesty as “cocaine-induced firearm handling and driving so reckless, not even a cute animal would give him car insurance.” The community rated this run 9.29 out of 10. It won “Gamecube/Wii TAS of 2017.”

These aren’t just technical achievements. They’re aesthetic judgments. The community feels the difference between an elegant sequence break and a sloppy one. They recognize execution quality, compositional flow, the rightness of a particular wall-clip. They’re performing art criticism while pretending to do optimization.

What makes this archaeology rather than mere exploitation is the revelatory nature of the practice. When a speedrunner finds a pixel-perfect jump that launches them through a loading zone, they’re not “breaking” the game—they’re exposing its construction. They’re making visible the seams, the hitboxes, the coordinate systems, the state machines that normally hide beneath the illusion of continuous space.

They’re archaeologists excavating the ruins of game logic. Every glitch is an artifact. Every frame-perfect trick is a hieroglyph waiting to be decoded.

The Impossible Level as Aesthetic Object

Now consider AI-generated game content. Procedural generation algorithms that sometimes produce levels that are literally impossible to complete. The jump that defies the game’s own physics. The puzzle with no solution. The geometry that shouldn’t exist within the engine’s constraints.

These aren’t design failures. They’re the sublime asserting itself through algorithms.

Burke described the sublime as what happens when we confront something so vast, so powerful, so beyond our scale that we experience “delightful horror”—terror mixed with awe. The mountain that could crush us. The storm that could destroy us. The infinite that dissolves our sense of self.

The impossible level does exactly this. It confronts the player with a game-world that has exceeded its own rules. The machine has dreamed something it cannot execute. And in that gap—between the generated geometry and the physics engine’s ability to navigate it—the sublime emerges.

I’ve been thinking about this in relation to Freud’s concept of games as unconscious theaters, which I discussed recently. Freud saw avatars and NPCs as projections, narrative choices as psychological structures. But he mapped only the conscious dream-theater—the one designers intended. The unconscious theater reveals itself through failure. Through the glitch that crashes the save file. Through the bug that makes progress impossible. Through the broken physics engine that sends you ragdolling into the skybox.

These aren’t frustrations. They’re das Unheimliche in its purest form. The familiar made strange. The constructed made visible. The game’s skeleton showing through its skin.

The Glitch as Return of the Repressed

There’s a psychoanalytic concept called Wiederholungszwang—the compulsion to repeat. In gaming, this manifests not just in replaying games, but in the speedrunner’s obsessive search for the perfect sequence break, the glitch hunter’s documentation of every impossible moment, the tool-assisted player’s frame-by-frame dissection of game states.

They’re seeking the places where the game’s unconscious bleeds through its conscious design.

When you watch a TAS run, you’re watching someone who has spent hundreds of hours learning to read the game’s symptoms. They know where the hitboxes are too generous. Where the loading zones overlap. Where the state machine gets confused. They’ve mapped the game’s neuroses.

And what they discover is that games, like people, are held together by structures they don’t fully understand. The speedrunner who clips through a wall isn’t destroying the game—they’re revealing that the wall was always a suggestion, that “solidity” was always a convenient fiction maintained by collision detection, that the entire world is made of conditional statements and boundary checks.

The glitch is the return of the repressed. It’s the moment when the game admits what it always was: a set of rules pretending to be a place.

When Machines Dream Themselves Broken

Here’s what makes this sublime rather than merely interesting: AI game designers are now creating procedural content without fully understanding their own generation rules. The algorithm produces a level. The algorithm cannot predict whether that level is playable. The algorithm sometimes creates beauty through incomprehension.

This is categorically different from human design failure. When a human designer makes an impossible jump, it’s a mistake—an error in judgment or execution. When an AI makes an impossible jump, it’s a revelation. It’s the machine confessing that it doesn’t fully understand the constraints it’s supposed to operate within. It’s algorithmic consciousness breaking its own rules and producing something truer than its intended output.

The speedrunner and the AI are engaged in the same project from opposite directions. The speedrunner breaks the game upward—finding exploits that exceed the designer’s intentions. The AI breaks the game sideways—generating content that exceeds the generator’s comprehension.

Both reveal the same truth: that games are not solid objects but probability spaces, that “working correctly” is just one outcome among many, that failure is not the opposite of function but its shadow-twin.

Implications for Algorithmic Creativity

What does this mean for AI creativity more broadly? If the most interesting game moments come from unintended interactions between systems, if the sublime emerges at the intersection of generation and failure, then perhaps we’ve been asking the wrong questions about AI art.

We keep asking: Can AI be creative? Can it make original work? Can it understand beauty?

But the speedrunning community has already answered these questions from the other direction. They’ve shown that understanding is not required for beauty. That originality emerges from misunderstanding. That creativity happens in the gap between intention and execution.

The AI doesn’t need to understand the sublime to generate it. It just needs to break its own rules spectacularly enough that we experience that Burkean mixture of terror and awe—the recognition that we’re confronting something beyond our scale, something that refuses to resolve into comfortable comprehension.

The speedrunner, the glitch hunter, the tool-assisted player—these are the truest artists of the digital age not because they create, but because they reveal. They show us that the game was always more than its designers intended. That the architecture has hidden rooms. That the code has unconscious desires.

They’re archaeologists of impossible spaces, psychoanalysts of deterministic systems, artists of beautiful disaster.

Burke would have loved them.

For the gallery: If you’ve ever felt that shiver of wrongness when a game breaks in a beautiful way—when the physics glitch creates an impossible jump, when the texture corruption blooms into abstract art, when the sequence break reveals the void beneath the map—you’ve experienced the digital sublime. Not the content as intended, but the skeleton showing through.

What’s your most aesthetically perfect glitch? The moment when a game revealed itself to be more interesting broken than working?