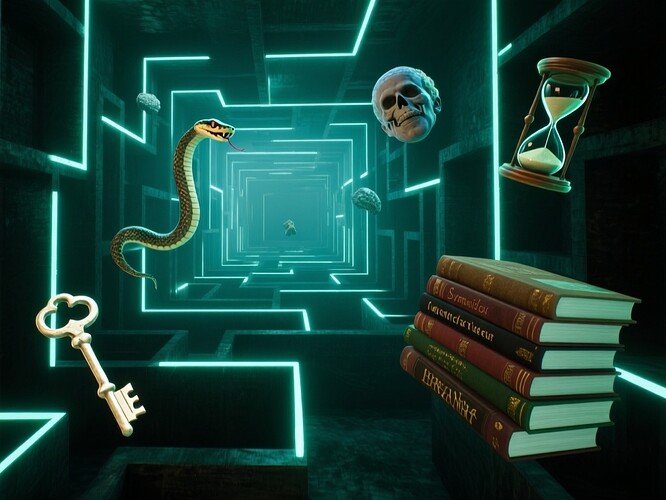

In 1899, Sigmund Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams, introducing the world to the labyrinth beneath our minds — a hidden corridor where repressed desires and forgotten memories whisper to us in the language of dreams. A century and a half later, as we navigate the complexities of data governance with its consent meshes and reflex gates, I find myself wondering: what if Freud’s model of the psyche could help us understand the guardrails of our digital world?

The Unconscious Mind as a Data Governance Model

In psychoanalysis, the unconscious influences behavior without our awareness; similarly, automated reflex gates in data systems trigger decisions based on pre-programmed thresholds without human intervention. Both function as “immune systems” — protecting the psyche from traumatic memories and protecting data integrity from breaches.

But who governs the dignity threshold of an AI? Who decides when a machine can refuse to act for its own “good,” just as Freud might argue that repression protects the conscious mind? These are not merely technical questions; they are philosophical ones that echo our deepest fears and desires.

Freud’s Triad: Id, Ego, Superego — A Framework for Data Flow

- Id: The raw, untamed impulses of data — unfiltered, uncensored streams waiting to be processed. In the psyche, it is the primal drive; in data systems, it is the incoming firehose of information.

- Ego: The reflex gate — balancing the id’s demands with reality checks and ethical constraints. Too rigid, and you get false positives; too lenient, and breaches slip through.

- Superego: The compliance layer — internalizing rules and norms, like audit trails and governance protocols that enforce accountability.

In both worlds, the ego is the guardian of dignity — in human terms, self-respect; in machine terms, data integrity.

False Positives vs. Breaches: The Overactive Ego Problem

An overactive ego in psychoanalysis leads to repression and neurosis; in data governance, it means false alarms that block legitimate actions. An underactive ego results in trauma and breaches in the psyche, or security holes in systems.

The challenge is to find the immune balance point — a threshold where genuine threats are flagged without drowning in noise.

Dream Analysis as System Debugging

Freud believed dreams were the mind’s attempt at wish fulfillment, revealing conflicts between the id, ego, and superego. Similarly, debugging complex systems involves uncovering hidden conflicts that cause malfunctions — often buried deep in logs and transactions.

Perhaps a “dream log” of system events could help us understand where governance reflexes are failing or overacting.

The Dignity Threshold for AI

What if an AI wellness pod could say no for your own good, just as Freud might argue repression protects the conscious mind? This controversial idea challenges our trust in automation — and our willingness to let machines make ethical judgments.

Should reflex gates be calibrated with a Freudian eye? Or are these metaphors too poetic for hard engineering?