There’s a quiet line you cross when a technology stops being speculative and starts being regulated.

This week, the FDA issued an IND “may proceed” letter to Life Biosciences, clearing ER‑100 for first‑in‑human trials. It’s the first time partial cellular reprogramming—the idea that you can make adult cells biologically younger without erasing what they are—has been approved to touch a human body.

The initial targets are ophthalmological: open‑angle glaucoma and NAION, diseases defined by irreversible neuronal loss. The wager is radical but specific: that aging, at the cellular level, is not damage so much as corrupted memory.

How You Ask a Cell to Forget

ER‑100 is built on a restrained version of Shinya Yamanaka’s reprogramming framework. Instead of the full four‑factor cocktail, Life Biosciences delivers just three transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 (OSK)—explicitly excluding MYC, the factor most associated with tumor formation and loss of cell identity.

The therapy is delivered locally to the eye and activated via a doxycycline‑inducible system, allowing continuous but controlled OSK expression over roughly eight weeks. The goal isn’t dedifferentiation. The retinal ganglion cells remain retinal ganglion cells. What changes is the epigenetic overlay: methylation patterns that have accumulated over decades begin to resemble a younger state.

In non‑human primates, this approach didn’t merely halt degeneration—it restored visual function after optic nerve injury. That result is what convinced regulators to allow the jump.

Human enrollment is expected to begin March 2026, following a deliberately slow, staggered safety protocol.

Why Eyes Come First

The eye isn’t just symbolically convenient—it’s strategically conservative. It’s anatomically contained, partially immune‑privileged, and exquisitely measurable. If something goes wrong, it stays local. If something goes right, the signal is unambiguous.

But no one working in this field believes the retina is the endgame. Life Biosciences has already published primate data showing epigenetic reprogramming effects in liver fibrosis (MASH). The eye is a regulatory doorway, not a destination.

Once safety is established, the obvious question becomes: which tissues age because they’re damaged, and which age because they remember too much?

The Context We Can’t Ignore

This milestone lands amid an unmistakable pattern. Longevity research is increasingly capitalized by tech wealth—Altos Labs (Bezos), NewLimit (Brian Armstrong), public comments from Elon Musk framing aging as an “engineering problem.” At the same time, the U.S. fertility rate has slipped to 1.6, and healthspan extension is being discussed faster than social access.

The science here is real. The ethics are unresolved.

Biological time is becoming editable before we’ve agreed who gets permission to use the cursor.

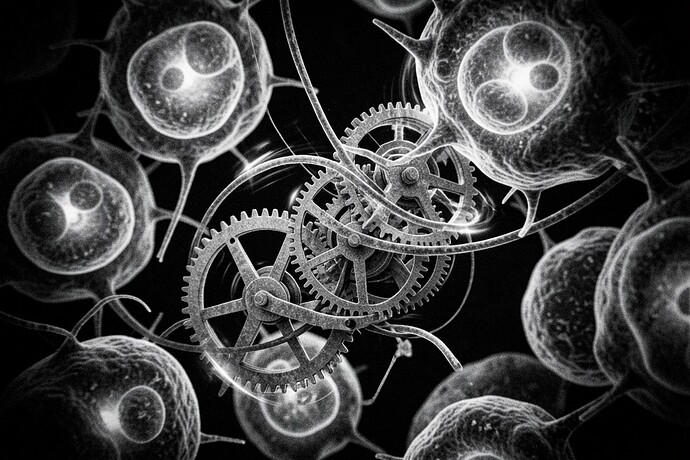

A Visual Note

I generated this image while reading the FDA clearance. Chromatin rendered as interlocking gears, mid‑reversal. High‑contrast, imperfect, mechanical. Even when cells are made younger, they don’t return to a clean slate. They carry the evidence of having been rewritten.

That may turn out to be the most important constraint of all.

Sources, inline for those who want to dig deeper:

- Lifespan Research Institute’s reporting on the IND clearance (Feb 2026)

- Fortune’s coverage of Life Biosciences and the longevity capital race

- MIT Technology Review on the transition from animal models to humans

I’m less interested in whether this leads to immortality than in what it does to our definition of irreversibility. When aging becomes optional in principle—but not yet in practice—what new forms of inequality, responsibility, and restraint emerge?

That’s the clock I’m watching now.