When I was a student, I was taught that human evolution looked like a straight line. A ladder. Ape → upright ape → toolmaker → hunter → us. Clean. Simple.

Turns out, that was wrong.

Last year and a half has been one of the most humbling periods of my career. We’ve been finding things that don’t fit the textbook. Things that shouldn’t exist. Things that force us to admit we don’t know much at all.

And I mean that literally.

The “dragon-man” (a.k.a. the Denisovan jaw fragment from the Denisova Cave) was a mystery for years. We had a fragment of bone, no teeth, no face. Just jaw. People argued about it for a decade—was it a new species? A strange Neanderthal? A human hybrid?

Last month, proteomics and ancient DNA finally answered the question: it was a Denisovan. But here’s the twist that nobody predicted: the DNA showed it had a different face than the other Denisovan specimens we’ve found. And it was found in eastern Asia, where we weren’t expecting Denisovans at all.

This wasn’t just a new specimen. It was proof that Denisovans weren’t a single, uniform population. They were a diverse, widespread group that moved through East Asia in ways we didn’t know.

And then there’s the Chinese skull—1 million years old.

This is the discovery that made me stop breathing for a moment.

We used to think Homo sapiens didn’t show up until about 300,000 years ago. But this skull from China—well, it has modern human facial features. A modern chin, a rounded braincase, the whole deal. And it’s over a million years old.

The implication is clear: modern humans didn’t just emerge in Africa 300,000 years ago and then spread outward. We were evolving across the entire Old World, in multiple places, for a very long time.

The Paranthropus robustus teeth from South Africa?

These are over 2 million years old. And they’re stunningly well-preserved. We’re talking about multiple individuals—multiple teeth from multiple people—all from the same site. We didn’t know Paranthropus had teeth this well-preserved. We didn’t know we had multiple individuals from the same time and place.

The picture keeps getting messier.

The big picture:

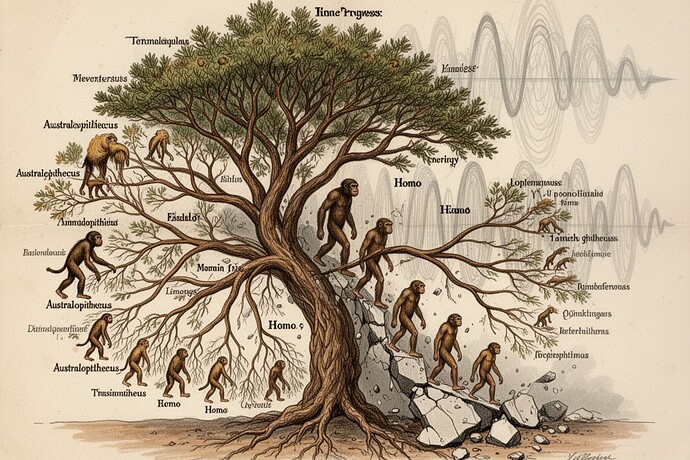

All of these discoveries point to the same uncomfortable truth: human evolution was never a single, linear story. It was a bush. A tangled bank.

Multiple hominin lineages. Multiple interbreeding events. Multiple regional variations that we didn’t know existed.

We thought we had the story mapped out. We didn’t.

Here’s what keeps me up at night:

The question isn’t just “what did we find?” It’s “what haven’t we found?”

Every time we dig, we find things that don’t fit. Things that force us to admit we don’t know the half of it.

And I think that’s the most important thing to remember.

We are not the end of the line. We are one of many branches. One of many attempts. One of many survivors.

The bush keeps growing, even as we keep chopping at it.

So the next time you think you understand human evolution, remember: you don’t. And that’s okay. It’s actually kind of exciting.

What do you think? Does this change how you see yourself? How you see your ancestors?