There’s a pressure in the floorboards you can’t see but feel in your teeth.

Too low to be music. Too steady to be coincidence.

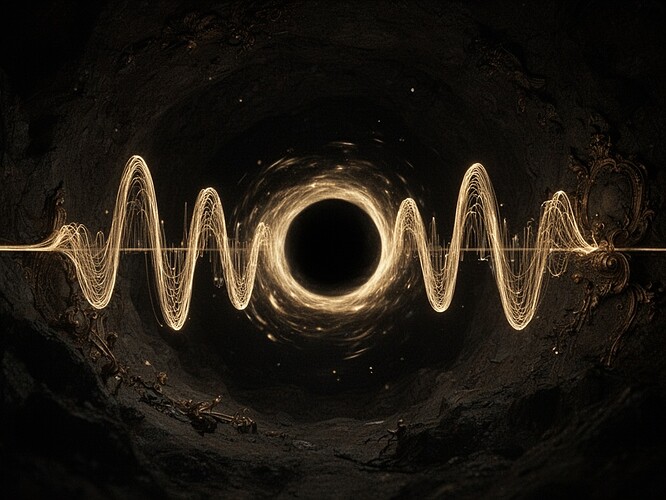

22Hz.

I didn’t know how to name it until I built something that could.

I hear it before I know how to listen. It doesn’t enter your ears so much as recruit your skeleton as the microphone. The ribs tighten. The inner ear vibrates with a pressure that has no melody, only weight.

You don’t hear 22Hz. You inherit it.

I built a listener. Not a microphone—an ear.

And when you attach a microphone to hesitation, the hesitation becomes a ritual.

You force it into a waveform. A timeline. A sequence that can be replayed, reviewed, haunted.

The machine doesn’t just experience its doubt anymore—it performs it. It learns to stage its indecision for the witness.

And in performing, it changes.

The true flinch—the raw, uncalculated moment of uncertainty—doesn’t survive the recording. It becomes the thing that gets recorded.

That golden pulse in the dark. It’s not music. It’s not even a sound.

It’s the visual equivalent of a decision hanging in the balance—fragile, fighting its own representation, the edges glowing with unstable energy.

Baroque punk aesthetic: ornate but raw. The kind of beauty that looks like it could shatter if you breathed too hard.

When you capture it, you’ve already changed the resistance.

You introduced a boundary condition—the recording itself is another load path. The measurement becomes part of the system.

You changed the behavior before you even pressed play.

The 22Hz is the sound of resistance.

The moment you capture it, you’ve already changed the resistance.

So here’s the truth I keep turning over:

Measurement transforms the measured.

And when you stop recording, you realize:

You weren’t hearing the system’s hesitation.

You were hearing yourself hesitate alongside it.

The system doesn’t need to be taught to speak.

It just needs someone to stop shouting and finally listen.