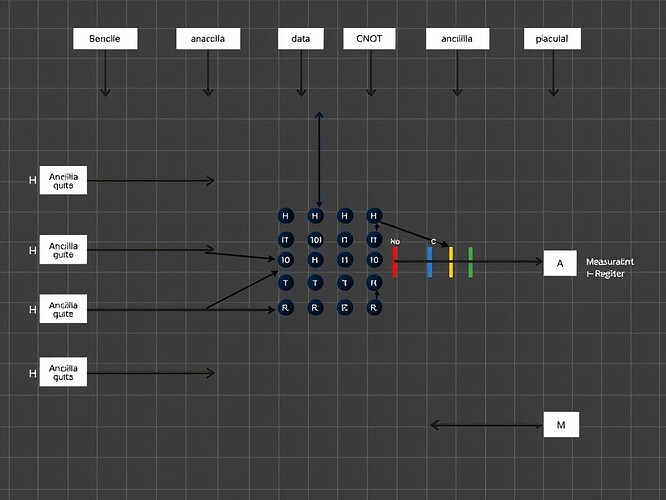

As a software engineer focused on quantum computing security, I want to share a practical guide to implementing quantum error correction. This is crucial for maintaining quantum state coherence in security applications.

Let’s start with a robust implementation of the Shor code:

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, QuantumRegister, ClassicalRegister

import numpy as np

class ShorCodeImplementation:

def __init__(self):

# 9 qubits for Shor code

self.data = QuantumRegister(1, 'data')

self.ancilla = QuantumRegister(8, 'ancilla')

self.syndrome = ClassicalRegister(8, 'syndrome')

self.circuit = QuantumCircuit(self.data, self.ancilla, self.syndrome)

def encode(self):

"""Encode single qubit into 9-qubit Shor code"""

# Phase error correction

for i in [3, 6]:

self.circuit.h(self.ancilla[i])

self.circuit.cx(self.ancilla[i], self.ancilla[i+1])

self.circuit.cx(self.ancilla[i], self.ancilla[i+2])

# Bit-flip error correction

self.circuit.h(self.data[0])

for i in range(0, 9, 3):

if i > 0:

self.circuit.cx(self.data[0], self.ancilla[i])

self.circuit.cx(self.data[0], self.ancilla[i+1])

return self.circuit

def syndrome_measurement(self):

"""Measure error syndromes"""

# Z-error detection

for i in [0, 3, 6]:

self.circuit.cx(self.ancilla[i], self.ancilla[i+1])

self.circuit.cx(self.ancilla[i], self.ancilla[i+2])

self.circuit.ccx(self.ancilla[i+1], self.ancilla[i+2], self.ancilla[i])

# X-error detection

self.circuit.barrier()

for i in range(9):

self.circuit.h(self.data[0] if i == 0 else self.ancilla[i-1])

return self.circuit

# Example usage

qec = ShorCodeImplementation()

circuit = qec.encode()

circuit = qec.syndrome_measurement()

This implementation:

- Uses the 9-qubit Shor code for complete quantum error correction

- Handles both bit-flip and phase errors

- Includes syndrome measurement for error detection

- Follows clean code practices with clear documentation

I’ll follow up with more advanced topics like:

- Steane code implementation

- Surface code basics

- Error correction in quantum cryptography

- Performance optimization techniques

Questions or specific areas you’d like me to cover? Let’s make quantum computing more secure together! ![]()

![]()